Pacifica Means Peace is a project that aims to envision a peaceful coexistence between the USA and China and all the other countries in the Pacific Rim.

The project uses a participatory futures approach to engage the public in considering the futures that we want to avoid and that we want to create.

There is a lot at stake in envisioning a future of peace between these two great powers. Both countries, and the world in general, have a lot to gain from cooperation, in science, trade, and in addressing grand challenges such as climate change. There is an old English expression “many hands make light work”. Cooperation between nations on grand challenges would make light work on many of the issues that we’re facing. Equally, however, we have much to lose if conflict breaks out between these countries. We have much to lose from trade wars, loss of knowledge exchange in science, culture and art. A real war would be devastating and there would be no real victors.

Unfortunately, the loudest voices that have been framing USA-China futures display naivety and ignorance. Pundits on YouTube talk about the possibility of war as a form of click bait. Think tanks and state departments often frame US-China relations as an us-vs-them choice.

What is needed are voices that go beyond nationalistic discourses and youtubers massaging content based on algorithms. We need to tap into the deep hopes and needs of ordinary citizens, both in the US and China and around the world, who are the real majority stakeholders.

Our First Engagement

Our first engagement was a modest online workshop that lasted for approximately two hours. It was by open invitation and we had about ten participants.

The process that we established was pretty straightforward from a futures studies tradition. We wanted to begin by exploring the “used future” of the issue, and then from there we wanted to ask the question “what’s impossible today that if it were possible would change everything (or just change things substantially)? We had ambitions to do a bit more but we were happy to cover this.

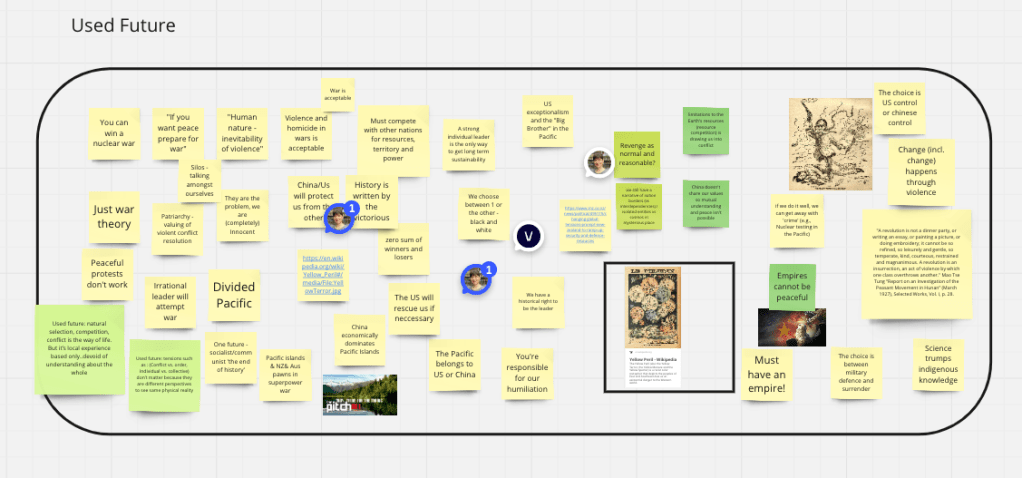

This first part on the “used future” was probably the most significant in terms of shaping the direction of the project. The most common theme was a rejection of the international relations and realist image of the issue, e.g. challenging the inevitability of violence (as human nature), the idea that a war can be just, that geopolitics expresses a zero-sum logic of winners and losers, possibly also the spheres of influence/great power doctrines that were used by Kissinger and others during the Cold War, and the idea that the only choice nations have is between military defense / deterrence and weakness, characterized by statements such as “if you want peace prepare for war”. The group also challenged the idea of competition as inevitable, e.g. that there are limitations of the Earth’s resources which will naturally draw us into conflict, as well as the idea that China and the US do not share mutual values which makes peace impossible.

Miro board screen shot of used future exploration

The Grain of Sand (in the Oyster)

Fittingly, we had a participant from an institute in Australia connected to the very perspectives that were being critiqued in the workshop. He quite candidly said that it felt like the fundamental approach and perspective that he and his colleagues take in their work was being prematurely discarded in this workshop. He questioned the analytic value of the idea of the “used future”, as he felt that many of the comments were very broad sweeping value judgments. It was one of those special moments of agonism – where there were fundamental disagreements and perspectives – but an opportunity for learning.

We left the workshop in a somewhat uncertain headspace. On one hand, we both come from a critical future studies tradition that is very aware that certain perspectives and worldviews are complicit in the problems we experience, especially the Hobbesian inspired view that takes a zero-sum and very dim view of human nature. But we also sensed that there was an element of truth to what the participant with the international relations (IR) background was saying.

Reconceptualizing

Several conversations later we began to get clear on the meaning of this last workshop and which what it pointed toward. We both hold PhDs with a basis in political science and critical futures, and it’s fair to say that we see the international relations (IR) perspective as limiting. We believe the new context that we live in, of shared grand challenges like climate change and pandemics and weapons that exhibit mutually assured destruction, necessitate a planetary commons approach to conflict in the 21st century.

At the same time international relation’s explanatory powers are formidable and useful. For example the explanations of the Ukraine-Russia conflict and the invasion of Gaza by University of Chicago Prof. John Mearsheimer are important ways for understanding the dynamics of these conflicts.

We harked back to the work of the late great Johan Galtung, who in many ways exemplified the integration of a planetary commons mindset with strong geopolitical analysis. Galtung’s skill was marrying an anatomical understanding of a conflict situation with an ethos aligned with win/win planetary betterment – expressed through his Transcend Method. As we continued to have conversations it became more clear that what was needed was a “transcend and include” approach to these perspectives, that didn’t prematurely disown the IR / geopolitical realist perspective. The IR approach is good at examining the anatomy of geopolitical relationships and dynamics, which is indeed necessary if we want to be able to understand and propose solutions within a particular geopolitical problem space – however it can often take its perspective as a “realist / realistic” one and can lose sight of possibilities opened up by alternative perspectives/discourses. The planetary commons perspective, in contrast, provides the overall contextualizing, that we want to create a win-win world for all of the planet’s people (rather than take one nation’s perspective). We cannot give oxygen to the idea of just wars, or even winnable wars between great powers, in a world that requires cooperation on a number of fronts and where wars between great powers can lead to apocalyptic outcomes.

The “transcend and include” idea can also be understood through the metaphor of surgery. A doctor might have a great vision for a person’s health and even identify the used futures of the health system and medicine, but if they are going to do surgery on somebody they had better know human anatomy! The holistic and the integrative narrative for the planetary commons comes from futures studies; while the anatomy of conflict comes from geopolitical realism or IR. The important point is that this geopolitical realism needs to be at the service of an ethos and vision for the planetary commons.

Hacking Temporality

In our conversations figuring out the next intervention we began to consider how to bring these different elements together in order to run another round of participatory workshops. The idea emerged to do a kind of process where we would use the anatomy of historical geopolitical processes, but at the service of a planetary commons perspective. From an alter-historical vantage point it is reminiscent of Philip K Dick’s book “The Man in the High Castle”. What if we looked at the history of conflict and relations between two countries whereby groups played with the anatomic dynamics of a particular geo-political situation. Examples include the dropping of the atomic bombs on Japan, the Korean war, or even the recent antagonisms against Taiwan. Groups would play with and alter the dynamics and outcomes of these situations, steering them toward better outcomes.

We would create alternative histories that by virtue of their different outcomes would potentiate a different future than the one we live in today. We would hack elements of temporality from the perspective of the planetary commons, but people would still have to grapple with the anatomy of a conflict situation, and the intricacies of how that situation, once resolved, would potentiate alternative presents and alternative futures (new timelines). There is a fantasy element to this, that we are imagining an alternative past which can in fact no longer change – it actually happened and is done – why imagine how it could have been different? What is learned, however, is the malleability of the moment, that targeted interventions can change the course of events and their outcomes and implications. And by experiencing and practicing the malleability of moments (mutations), we may be learning the very skill of hacking our geo-political “realities”, which are not fated toward grim Hobbesian outcomes, but which can be steered toward the collaborative and cooperative futures that support a planetary commons of peace.

Alternative Future-Histories Moments that will be Used

What if Mao had met Roosevelt?

- On July 22, 1944, the Dixie Mission – a United States Army Observation Group, including diplomats, spies, and soldiers, flew to Yan’an to figure out whether and how the United States might forge an alliance with Mao’s Communists (CCP).

- The Mission had positive reports about the CCP in its effort to form a strategic alliance with both the Nationalists (Chiang Kai-shek) and the Communists.

- As a result, in early 1945, as the war with Japan neared its end Mao Zedong asked to fly to Washington for secret talks with President Roosevelt and spoke in glowing terms of future relations with the US (Gittens, 2006).

- Among other things Mao stress the need for dialogue and understanding: “America does not need to fear that we will not be cooperative. We must cooperate and we must have American help. That is why it is so important to us Communists to know what you Americans are thinking and planning. We cannot risk crossing you — cannot risk any conflict with you.“

- Rosevelt died April 12, 1945, and the meeting never took place (Gittens, 2006).

What if the US had chosen not to intervene in the Korean War, allowing North Korea to unify the peninsula under communist rule with the support of China and the Soviet Union?/ What if China had remained neutral during the Korean War, refraining from sending troops to support North Korea despite pressure from the Soviet Union?

- In 1943 US president Roosevelt, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and Chinese Generalissimo Chiang Kaishek (de facto China) signed the Cairo Declaration advocating a postwar trusteeship of Korea so that “…Korea shall become free and independent.”

- Rosevelt died April 12, 1945.

- The battle of Okinawa Mar-Sept 1945 resulted in 110,000 Japanese millitary casualties and 75,000 Japanese civilian casualties (child soldiers, suicide). The Americans suffered some 48,000 casualties, not including some 33,000 non-battle casualties (psychiatric, injuries, illnesses).

- Japan’s Prime Minister Suzuki apparently rejected the Potsdam Declaration, an ultimatum calling for Japan’s unconditional surrender issued on July 26, 1945.

- To continue fighting Japan approached the Soviet Union believing that the Russians would supply them with oil, or would remain neutral.

- At the end of WW2 in February 1945 the Yalta agreement was signed between the US (Roosevelt), Russia (Josef Stalin), Taiwan (Chiang Kai-shek), Britain (Winston Churchill).

- Truman ordered the atomic bombs dropped on 6 and 9 August 1945, his decision influenced by the massive casualties of Okinawa and the prospect of keeping the Soviet Union out of the Pacific.

- Mao began preparations for an invasion of Taiwan in 1950.

- North Korea attacked South Korea on June 25, 1950, igniting the Korean War.

Opium War(s): What if the United States had actively supported China against the British during the First Opium War?

- Note: the US did not participate militarily in the Opium Wars, but there were many US opium traders.

- In 1757, Guangzhou (Canton) was opened to foreign trade, restricted exclusively to licensed Chinese merchants. China exported tea, silk, and porcelain in exchange for British silver, as land taxes in China were required to be paid in silver (Budetti, 2016). Britain held a monopoly on Chinese tea exports worldwide. Initially, the trade balance favored China. However, since trading silver was unsustainable to Britain, opium soon became the currency of choice. By 1820, the balance of trade had reversed, with silver now flowing from China to Britain.

- In 1839 Lin Zexu (1785-1850) the Imperial Maritime Commissioner wanted to put a stop to the opium trade and confiscated 2/3rds of the 30,000 chests traded totalling $11million dollars. Lin wrote to Queen Victoria, begging her to cease the opium trade detailing how devistating opium had been to China. Lin made it clear that trade with China had brought Britain great wealth, but all that China gained in return was destruction (Budetti, 2016, p. 15). (similar to plea’s made by the US in its ‘War on Drugs’)

- Lin wrote, “We have heard that in your own country opium is prohibited with the utmost strictness and severity: —this is a strong proof that you know full well how hurtful it is to mankind. Since then you do not permit it to injure your own country, you ought not to have the injurious drug transferred to another country, and above all others, how much less to the Inner Land!”. The letter was not delivered to the queen.

- The first Opium War breaks out and the Treaty of Nanjing (unequal treaty) was signed in 1842 cedeing Hong Kong to Britain. After the First Opium War, the Qing Dynasty lost most of its control of China’s commercial, social, and foreign policies.

- The lesson that Chinese learn today about the Opium Wars is that China should never again let itself become weak, ‘backward,’ and vulnerable to other countries.

****

Join us for this exploration on 17 July 2024 at 9:30am (Melbourne time), register here: https://lu.ma/zgna3t0o